www.gauntantik.com

JAMES, Henry (illustrated by Peter MILTON)

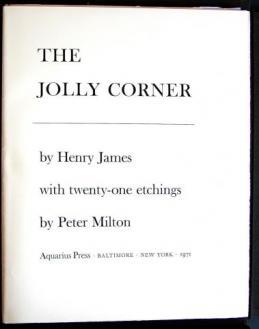

“The Jolly Corner”

Baltimore and New York: Aquarius Press, 1971

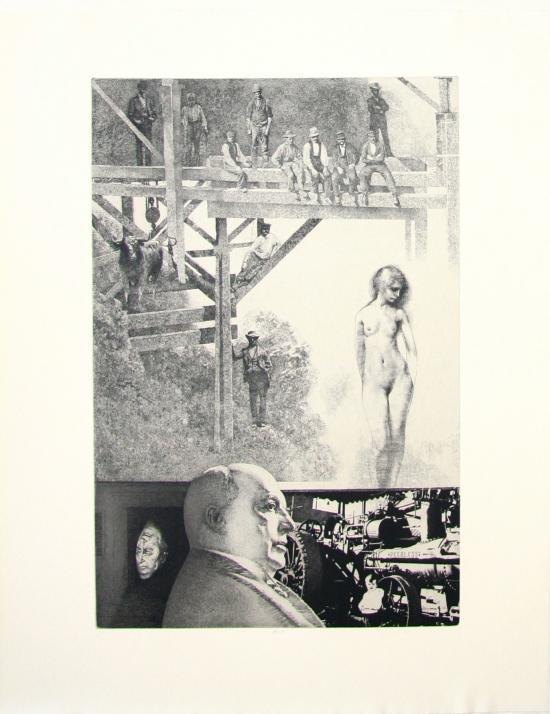

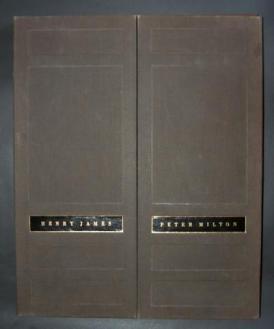

First free-standing edition, after antecedent issues in magazine and collection formats. Embossed dark grey-brown linen double clamshell case with letterpress text and 21 resist-ground etchings with engraving by Peter Milton, case 20-1/8 x 16-1/2 in., text leaves 19-1/2 x 15-7/8 in., etchings on sheets 15 x 19 in. (38.1 x 48.3 cm), the images 9-3/4 x 14-3/4 in. (24.7 x 37.5 cm) from copperplates 10 x 15 in. (25.4 x 38.1 cm). One of 150 copies on Rives (the etchings on Heavyweight Buff) from the total limitation of 184, signed by Milton and numbered 3/150 on the colophon page. The text fascicle collates 9 loose folios: 1 l. (front cover, title recto, copyright notice verso), 1 l. (half-title recto) and [1 l.], comprising a folio folder for Plate II-2 as frontispiece (if repositioned from second print fascicle), 6 ff. (pp. 7-28, with two blank pp.), 1 l. (p. 29 recto) and 1 l. (colophon recto), 1 l. (rear cover, half-title recto). Three print folders I, II and III corresponding to the chapters (text excerpts on each first leaf recto), each fascicle folio containing seven loose prints (plate II-2, signed by Milton, intended to be inserted as frontispiece in the second text folio). Robert Townsend and Gretchen Ewert pulled the etchings at Impressions Workshop in Boston under the supervision of the artist. The Press of A. Colish in Mount Vernon printed the letterpress. The front cover of the case is embossed with the double door motif taken from Plate III-3, each half with a gilt-ruled black morocco label lettered in gilt respectively “HENRY JAMES” and “PETER MILTON.” Slight scuffing and rubbing of case cover cloth, all else fine. McNulty 62-82.

“The Jolly Corner” was first published in The English Review, vol. 1, no. 1 (London, December 1908), and was included as parts of The Novels and Tales of Henry James, vol. XVII (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1909) and The Uniform Tales of Henry James (London: Martin Secker, [1919]). This magnificent production of the Aquarius Press and Peter Milton is the first free-standing edition of this “ghostly tale,” given concluding place in Harold Bloom’s selection of four archetypal James works in The Daemon Knows (New York: Spiegel & Grau, 2015). “Henry James,” Bloom prefaces, “the master of his art, nevertheless congratulates his own daemon for the greatest of his novels and tales.” Milton understands this in depicting the protagonist Spencer Brydon: in Chapter III it is James himself at the time of writing. (Milton’s image may be compared with James in the 1905 photographs by Coburn and McClelland and Sargent’s oil portrait of 1913. Who are Brydon’s stern forebears in Plate I-1? – might we discern the visages of Emerson and Hawthorne? )

“The Jolly Corner” is a tale first (Chapter I) about juxtaposition, the old world and the new, the hard “‘swagger’ things, the modern, the monstrous, the famous things,” confronting the “spirit,” “the perfection nothing else could have blighted,” of “a small still scene where items and shades, all delicate things, kept the sharpness of the notes of a high voice perfectly trained, and where economy hung about like the scent of a garden.” The questing, layering introspective tension, set overtly as a clash of architecture (always admirable symbol for the craft of authorship), is palpable: “If he had but stayed at home he would have discovered his genius in time really to start some new variety of awful architectural hare and run it till it burrowed in a gold mine.” “It isn’t that I admire them so much – the question of any charm in them, or of any charm, beyond that of the rank money-passion, exerted by their conditions for them, has nothing to do with the matter: it’s only a question of what fantastic, yet perfectly possible, development of my own nature I mayn’t have missed. It comes over me that I had then a strange alter ego deep down somewhere within me, as the full-blown flower is in the small tight bud, and that I just took the course, I just transferred him to the climate, that blighted him for once and for ever.”

The tale segues (Chapter II) into a hunt, a pursuit, a “craping up to thim top storeys in the ayvil hours” to stalk the ghost of Brydon’s alter ego, finally a recoil in horror from the actual encounter with “the hot breath and the roused passion of a life larger than his own, a rage of personality” that “fitted his at no point, made its alternative monstrous.” Then comes (Chapter III), perhaps – just perhaps – uniquely in James, a requited love story, cached as an awakening “of a man who has gone to sleep on some news of a great inheritance, and then, after dreaming it away, after profaning it with matters strange to it, has waked up again to serenity of certitude and has only to lie and watch it grow.” Miss Staverton, Brydon’s “old friend,” ripostes the notion that the strange ego-apparition, so odiously different, didn’t come to Brydon: “‘You came to yourself,’ she beautifully smiled. ...Her look was again more beautiful to him than the things of this world. ‘Haven’t you exactly wanted to know how different?’”

Different how? Brydon is visiting ancestral “annals of nearly three generations” after 33 years. The same number of years before writing “The Jolly Corner” James was at work on The American, at the onset of his transplant into “Europe.” The decade of the 1900’s beheld James’s glorious triad – The Wings of the Dove, The Ambassadors, The Golden Bowl. On the tails of Twain and Crane it was, as well, the muscled decade of Dreiser, Norris, London, the Muckrakers, “‘swagger’ things, the modern, the monstrous, the famous things.” Was James as good as all that? – Brydon poses to Miss Staverton in Chapter I. “‘Do you believe then – too dreadfully! – that I am as good as I might ever have been?’ ...‘Oh, no! Far from it! ...But I don’t care,’ she smiled. ‘You mean I’m good enough?’ She considered a little. ‘Will you believe it if I say so? I mean will you let that settle your question for you?’”

The suppressed and suspended answer, forged by the ensuing alternations with Brydon's ghost, bursts forth in the last chapter, the ultimate dialogue: “‘Ah!’ Brydon winced.... ‘But he hasn’t you.’ ‘And he isn’t – no, he isn’t – you!’ she murmured, as he drew her to his breast.’”